Connell Stamps

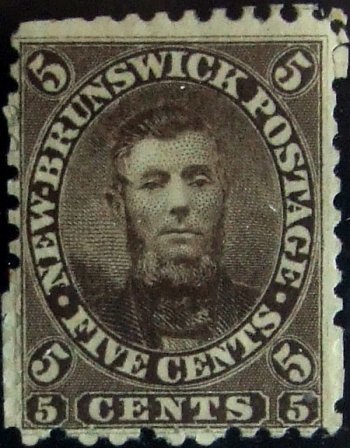

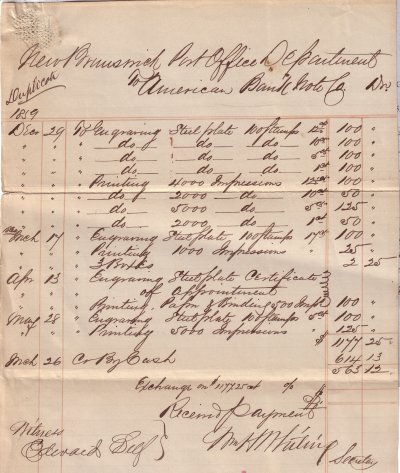

In anticipation of the transition to decimal currency, the Postmaster General was authorized by the Lieutenant Governor in Council to procure appropriate postage stamps. Mr. Connell chose the American Bank Note Co., New York, as the supplier, and on December 29, 1859, ordered 200,00 1-cent, 500,000 5-cent, 200,000 10-cent and 400,000 12½-cent stamps. The stamps were to be printed in perforated sheets of 100.

Nova Scotia also chose the American Bank Note Co. as their supplier, ordering postage stamps in the same denominations, each denomination bearing the likeness of the Queen. The Nova Scotia stamps were issued on October 1st, 1860.

The first adhesive-backed postage stamp, created by Sir Rowland Hill (1795-1879), was issued in Great Britain on May 6, 1840. The famous “Penny Black” was engraved with the profile of Queen Victoria, a design that continued in Great Britain throughout her reign.

In July, 1849, the British Parliament passed an “Act for Enabling Colonial Legislatures to Establish Inland Posts.” Postage rates on letters within British North America were set at 3 pence per half-ounce. The corresponding Act1, passed by the New Brunswick Legislative Assembly on 26 April, 1850, stated, “That the Lieutenant Governor in Council may cause postage stamps marked with any device thereon, and the words ‘three pence” to be engraved and printed . . . .” The 1851 amending Act2 contained nothing to change this clause. New Brunswick issued its first postage stamps, unperforated, on September 5th, 1851, in 3 pence, 6 pence and 1 shilling denominations.

New Brunswick and Nova Scotia stamps were engraved and printed by Perkins, Bacon and company, 69 Fleet Street, London, England. The same design, a Queen’s crown surrounded by four heraldic floral emblems, was used on all denominations. The Nova Scotia stamp added a mayflower, long a symbol of that Province, to England’s rose, Ireland’s shamrock and Scotland’s thistle. New Brunswick stamps employed the shamrock and thistle, with the image of the rose repeated.

Pre-payment of postage remained optional; the sender of a letter could still choose to let the recipient pay the postage cost.

Charles Connell was elected to the New Brunswick Legislative Assembly, as a representative of Carleton County, in 1846, to fill the vacancy created by the resignation of his half-brother, Jeremiah M. Connell, who had represented Carleton County since 18343. Charles was re-elected in the General Election of 1850, and was thus a sitting member of the House of Assembly when the 1850 Act, cited above, was passed.

The February 10th, 1859, edition of the Journal of the House of Assembly announced, “The House having been by several Proclamations prorogued until this day, then to meet for the dispatch of business; and being met— The Clerk of the Crown in Chancery delivered to the Clerk of the Assembly — Returns from . . . the Sheriff of the County of Carleton, to Writs of Election issued during the recess by reason of vacancies having occurred in the Representation for . . . the said County of Carleton, in consequence of . . . the Honorable Charles Connell having vacated his Seat by acepting the Office of Postmaster General.”

Mr. Connell was nominated as a candidate in the Carleton County election, held on Monday, November 15th, in which he was opposed by Leonard Harding. On the following Wednesday, Sheriff F. R. Jenkins Dibblee declared Mr. Connell elected, he having received 1,030 votes against Mr. Harding’s 599. Thus Charles Connell held a seat in the House of Assembly, a seat on the Executive Council, and the office of Post Master General simultaneously.

One of Charles Connell’s first acts, in his capacity of Postmaster General, was the institution of daily mail service between Saint John, New Brunswick, and Halifax, Nova Scotia.4

In anticipation of the transition to decimal currency, the Postmaster General was authorized by the Lieutenant Governor in Council to procure appropriate postage stamps. Mr. Connell chose the American Bank Note Co., New York, as the supplier, and on December 29, 1859, ordered 200,00 1-cent, 500,000 5-cent, 200,000 10-cent and 400,000 12½-cent stamps. The stamps were to be printed in perforated sheets of 100.

Nova Scotia also chose the American Bank Note Co. as their supplier, ordering postage stamps in the same denominations, each denomination bearing the likeness of the Queen. The Nova Scotia stamps were issued on October 1st, 1860.

The Hon. Charles Connell lived in a Greek Revival mansion in Woodstock, his residence furnished sumptuously with quality furniture — Hepplewhite, Sheraton and early Empire — good silver, and the brass andirons once owned by Benedict Arnold.5 Perhaps it should not be surprising that such a person would endeavour to inject some beauty in the postage stamps he ordered, in contrast to the mundane design of the earlier pence issue. The new 10-cent denomination bore the image of Queen Victoria, but the 1-cent stamp featured a wood-burning locomotive, reputed to be the Ossekeag, but more closely resembles the Coos, a 4-4-0 engine used on the Atlantic & St. Lawrence Railroad in the mid-1800s. The 12½-cent stamp displayed a paddle steamer, reputed to be either the Royal William, the first steamship to make the North Atlantic crossing, or the Washington, which carried trans-Atlantic mail between New York and Southampton from 1847 to 1858. Nicholas Argenti6 suggests the stamp image more closely resembles this latter vessel.

Apparently, Mr. Connell managed to keep the stamp designs secret until the shipments had actually been received. It is not clear when the new stamps arrived in New Brunswick, but on April 26th, The Morning Freeman7, a Saint John newspaper, launched a series of vitriolic attacks on the Postmaster General and the 5-cent stamp which bore his image. A rival paper, The Religious Intelligencer, was supportive of Mr. Connell and his stamp, dismissing it as “this trifling affair.”8 On April 27th, S. L. Tilley telegraphed Charles Connell, at Woodstock, “Just received notice from Governor that new decimal Stamp cannot be issued until approved by Governor in Council. — have seen Hale please Telegraph him he can put all right.” The following day, Mr. Connell sent a message to James Hale, “See Mr. Tilley Let issue of Stamps be stayed till Wednesday next,” that is, until May 2nd.

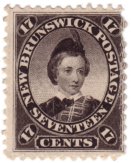

On the 8th of May, the Executive Council advised Lieutenant-Governor J. H. T. Manners-Sutton “to Approve of And order to be distributed, the one cent, ten cent, and twelve and a half cent Postage Stamps procured by the Post-Master General and we further advise Your Excellency to order a five cent Postage Stamp to be struck, bearing the likeness of the Queen, instead of the five cent stamp allready(sic) procured by the Post-Master General.”

It would seem some discussion arose from this memorandum, for the Lieutenant-Governor only acted on the Council’s recommendation four days later, when, on May 12th, he ordered, “The one cent, ten cent, and twelve and a half cent Postage Stamp, procured by the Postmaster General, to be distributed and a five-cent postage stamp to be struck bearing the likeness of the Queen.”

Seven days later, the Hon. Charles Connell submitted a 21-page letter, resigning his position as Postmaster General and his seat on the Council. The resignation was accepted immediately by the Lieutenant-Governor and the Executive Council notified accordingly.

While Mr. Connell’s letter of resignation is too long for inclusion, some sections seem worthy of mention. He stated, “That each Head of a Public Department should be left to the administer its duties as would in his judgement be most beneficial to the interest Public Interest and if his administrative ability be such and his action does not meet the concurrence of His Colleagues(sic) his duty is plain either to assent and give effect to the advice of His Colleagues or resign his office — each head of a Department should have the same responsibility to his Colleagues as they do to Your Excellency.” Continuing, he recited various instances where he criticized, or disagreed with, the action, or inaction, of the Council.

His only mention of the stamps appears at the end of the letter, and reflects the deterioration of his relations with the other members of the Council since his initial appointment: “the recent act of my Colleagues in the Govt has brought matters to a crisis — the want of that support on their part on a subject which I believed I was authorized in the action I had taken as will appear by the Following Minute of Council and Correspondence:—

“Postmaster General to obtain New Postage Stamps in one five and Ten & Twelve & half Cents.”

Mr. Connell offered no explanation for his portrait appearing on the 5-cent stamp. To his credit, he made no attempt to blame any other person for the act. As head of the Postal Department, authorized by the Lieutenant-Governor and Council to obtain new postage stamps, and supported by Section 9 of the 1850 Act, cited above, Charles Connell evidently considered he had full authority for his action.

James Steadman, Esq., was appointed Postmaster General and a member of the Executive Council on May 22nd, and within the week 500,000 5-cent stamps, bearing the image of Her Majesty, were ordered from the American Bank Note Company.

This replacement stamp became available in July, 1860, but in the interim, the 10-cent stamp, bisected, was used as a substitute.9

This replacement stamp became available in July, 1860, but in the interim, the 10-cent stamp, bisected, was used as a substitute.9

Although Charles Connell had resigned as Postmaster General and as a member of the Executive Council, he retained his seat in the Legislative Assembly as a representative of Carleton County. In the next general election, June 10, 1861, he was defeated, but regained his seat in the Assembly in 1864, and in 1866 was appointed Surveyor General of New Brunswick. The so-called “stamp scandal” apparently had little impact on Mr. Connell’s political career, for he continued to represent Carleton County in the New Brunswick Legislative Assembly until he resigned, in July, 1867, to contest the first federal election in September of that year. He was elected, by acclamation, and continued to represent Carleton County in the House of Commons until his death in 1873.

Charles Connell paid the cost of the 5-cent stamps and the plates from which they were printed. Argenti questions whether payment was actually made, since the payment never appeared in the accounts of the Postmaster General,10 but it seems highly unlikely that Mr. Connell was able to possess the stamps without making payment.

Mr. Connell gave full sheets (100 stamps each) to his daughters, Alice and Ella, and may have passed a few samples of the stamp to close friends.11 The gifts to Alice and Ella are confirmed by a letter from Alice, written some time after 1897, when she married Charles Garden and was living in Victoria, stating she had destroyed her sheet of Connell stamps and imploring Ella to do likewise.

An article on the Connell Stamp in the September-October 2000 issue of The Canadian Philatelist. includes the following statement:—

“Premier Tilley sent a young clerk of the House to round-up all the stamps, a Frederick Dibblee , who, years later, spoke freely of the affair. He admitted he had not destroyed a sheet of 100 and a single copy from one other sheet. But Dibblee may not have been terribly diligent in his search because he had married one of Charles Connell’s daughters, Ella. We know also from other correspondence that Charles Connell gave a sheet to his daughter Mrs. Dibblee, and one to another daughter, Mrs. Gardner(sic).”

The veracity of this tale is questionable.

Col. F. Herbert J. Dibblee, who married Ella Sophia Anna Connell, was born on 6 October, 1851, son of Sheriff F. R. Jenkins Dibblee. The Dibblee-Connell wedding took place at Woodstock on 3 June, 1896, long after the death of Charles Connell. S. L. Tilley was Premier of New Brunswick from 1861 to 1865, during which time Frederick Herbert Jenkins Dibblee would have matured from 10 to 14 years of age, tender years for an emissary of the Premier.

Dr. G. F. Clarke, who was well acquainted with Col. Dibblee, dismissed this story as a fable, adding, “in the first place, Colonel Dibblee was never, to my knowledge, a Queen’s messenger. though, if he was, I cannot imagine the peppery Mr. Connell handing over to a mere boy, nor anyone else, postage stamps that were his own property. Rather would he have shown them the door.”12

An interesting story13 appeared in the April, 1899, issue of Stanley Gibbons’ Monthly Journal, an extract of which follows:—

“A number of years ago I was in Woodstock, where Mr. Connell lived, and knew him well. On asking him about the celebrated ‘Connell’ stamp, he told me that what he felt most keenly about the affair was the charge of vanity urged against him. His explanation was, as well as I can remember, that it was necessary, as New Brunswick had followed Canada in adopting the decimal system, to change its designations of the New Brunswick postage stamps. As Postmaster-General, he had to carry out the change. He accordingly went to the United States to make the necessary arrangements. There were several denominations of stamps, and the design for each had been settled excepting that for the 5 cents stamps. Being obliged to return unexpectedly to New Brunswick before that design had been agreed upon, he urged the designer to give him something definite about it. The artist said if the matter was left to him he would let the Postmaster-General have something that he thought would please the people. Mr. Connell, ‘in a moment of weakness,’ agreed to the proposal and left for home. When the first consignment of stamps arrived he was more surprised than anyone else to find that the stamp bore his own likeness. He had not time to change the design so let it go. The day for the first issue came, and with it a storm of popular wrath, which the Premier of the day allayed by the only course open to him, viz., by requesting and obtaining Mr. Connell’s resignation.”

Mr. Connell’s “surprise” at his likeness on the stamp does not bear close scrutiny. While the American Bank Note Company was created in 1858, it was the result of a merger of seven printing and engraving firms whose histories went back to the late 1700s and early 1800s. It is inconceivable that the Company would fail to obtain approval of the designs of each New Brunswick stamp. That they did so is substantiated by the present existence of die and plate proofs. Some one in authority in the New Brunswick Post Office Department had to approve those proofs, and it is extremely improbable that Mr. Connell would have delegated that authority to any employee.

Nicholas Argenti, whose research was meticulous, states that a few of these proofs were found in Charles Connell’s office after he resigned.14

The anonymous narrator’s story continues:

“While Mr. Connell was giving me this version of the trouble we were walking in front of his house. He said, ‘I have the stamps here, for I felt that it was only right that I should pay for them out of my own pocket.’ Taking me into a room, he showed me a great pile of the stamps, and said, ‘I am going to burn them.’ Thinking that a souvenir would be a good thing to have, I asked him if he would let me have a few. He at once acceded to my request, and I put some of them in my pocket book. Soon after I learned that he had destroyed his little ‘Klondike.'”

Dr. G. F. Clarke was well acquainted with Alice and Ella Connell, and their husbands. He purchased the brick house Charles Garden had built in Woodstock when Charles and Alice Garden removed to Victoria, B.C. When the Gardens returned, some dozen years later, they lived with Alice’s sister, Ella, and her husband, Col. Dibblee.

Charles Garden and Ella Dibblee predeceased their spouses, and Col. Dibblee and Alice Garden continued to live in the grand house on Richmond Street. After Col. Dibblee’s death in 1933, Dr. Clarke purchased the contents of a shed on the property, a building which Col. Dibblee had used in his silversmith business. Searching for the handle of a silver teapot in the debris in that building, Dr. Clarke found the only known pair of Connell stamps. This pair of stamps eventually became part of the Argenti collection. Presumably, the pair had been detached from the sheet given to Ella by her father, and the remainder of the sheet was the only Connell stamps Col. Dibblee ever burned.

How many 5-cent Connell stamps exist? Estimates by various writers vary. Nicholas Argenti15 noted there were about 30 with Royal Philatelic Society certificates, and there are probably others certified by other Expert Committees. He suggests there may be about 50, “at a rough guess,” but cautions that perfect specimens are exceedingly rare.

But Ella and Alice Connell had a younger sister, Susan, who, at age 21, married George Anderson of Halifax on July 24th, 1867, seven years after the stamp affair. Did Charles Connall also give a sheet to Susan? If Susan did receive a similar gift, what became of them? That question does not appear to have been addressed in any article published to date.

Why did the Postmaster General’s image appear on the 5-cent New Brunswick stamp? Was it, as some writers suggest, mere vanity? Or perhaps at the instigation of some well meaning friend, or a devious political enemy who sought his destruction? The answer is apt to remain unknown. Whatever motive lay behind the 5-cent Connell stamp, Charles Connell deserves credit for the innovative designs of the other postage stamps in this first decimal series.

1. Acts of the General Assembly, 1850, 13 Victoria, CAP. XLIX, § IX.

2. Acts of the General Assembly, 1851, 14 Victoria, CAP I.

3. “Graves Papers,” Provincial Archives of New Brunswick.

4. The Postal History of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick 1754 – 1867, Jephcott, C. M., V. G. Greene, John H. M. Young, Sission Publications, Toronto, 1964, p. 112.

5. “Charles Connell and His Postage Stamps,” Clarke, Dr. George Frederick, The Atlantic Advocate, November, 1963, p. 45.

6. The Postage Stamps of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, Argenti, Nicholas, 1976, Quarterman Publications, Lawrence, Mass., p. 156.

7. The Postal History of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick 1754 – 1867, Jephcott, C. M., V. G. Greene, John H. M. Young, Sission Publications, Toronto, 1964, pp. 112-116.

8. Ibid, pp. 116-117.

9. Ibid, p. 118.

10. The Postage Stamps of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, Argenti, Nicholas, 1976, Quarterman Publications, Lawrence, Mass., p. 131.

11. “Charles Connell and His Postage Stamps,” Clarke, Dr. George Frederick, The Atlantic Advocate, November, 1963, p. 51.

12. Ibid., p. 50. In correspondence with Nicholas Argenti, previous to the publication of The Postage Stamps of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, Dr. Clarke debunked Col. Dibblee’s story and suggested it should be deleted from the manuscript. Mr. Argenti, however, let that section stand. See Argenti, p. 148.

13. See also Postage Stamps of New Brunswick, Poole, Bertram W. H., Severn-Wylie-Hewett Co., Beverly, Mass, Portland, Maine, n.d. (circa 1920), p. 13, and The Postage Stamps of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, Argenti, Nicholas, 1976, Quarterman Publications, Lawrence, Mass., p. 145.

14. The Postage Stamps of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, Argenti, Nicholas, 1976, Quarterman Publications, Lawrence, Mass., p. 148.

15. Ibid., pp. 151-2.